![]()

CHAPTER THREE

~ Other Saintly

Dragon Slayers ~

![]()

|

AS dragon slaying is a common allegory to express the triumph of the Christian hero over evil, quite a number of those commemorated in the Calendar of Saints are credited with having overcome some dragon or other monstrous enemy of the Christian religion. The Saviour Himself and the Virgin Mary, if not exactly numbered among the dragon slayers, are represented as trampling underfoot the Old Serpent of Evil. St. John the Evangelist is credited with charming a winged dragon from the poisoned chalice given him to drink. Even the Puritan writer John Bunyan avails himself of the same figure when he makes Christian encounter and prevail against Apollyan. In the early centuries of the Church's history, when Christendom was beset on many of its borders by various forms of gross heathenism, the opportunities of rising to the canonical degree of heavenly sanctity, by spiritual conquests over prevailing Evil, were always discoverable by the heroically inclined. So firmly was the idea of religious dragon slaying impressed on the minds of the early Christians that the consideration of it as an hereditary virtue, passing from father to son, seemed quite a reasonable proposition to entertain. So we have a Sicilian legend to the effect that this country was once ravaged by a monster called Pongo, which from time to time came up out of the sea, devoured hundreds of the inhabitants, and left the region desolate. After these depredations had gone on for a long time, the country was at last saved from further ravagings by three sons of the mighty champion St. George, who went forth with their father's valour and slew the amphibious monster. These saintly champions of old are peculiar to no Christian country, though ancient France seems to have been somewhat prolific of them. Thus St. Romain of Rouen destroyed a huge dragon called La Gargouille which ravaged the Seine ; St. Florent killed a similar dragon which haunted the Loire ; similar feats were performed in Brittany by St. Cadoc, St. Maudet, and St. Paull ; while on the eastern frontiers at Aix-la-Chapelle, the terrible dragon called Tarasque was slain by St. Martha. In England there is a legendary record of only one saintly dragon slayer - St. Keyne of Cornwall. St. Cadoc was born the son of a Welsh prince, but "entered religion" and became Abbot of Chepstow. St. Michael was not, like St. George, a mortal man, but an Archangel of heaven, mentioned in the Book of Revelation ; and in all pictures and representations of him he is to be distinguished from the latter by the presence of his angelic wings. But he is frequently represented as a dragon slayer, and when shown in actual combat it is always in the position of a conqueror, though the vanquished enemy may be depicted as a dragon or a serpent or a non-descript reptile of terrible aspect. In every case St, Michael appears as a fighting champion, though why in pictures of him it should be thought necessary to mount an angel on horseback is not quite apparent. Christian art, however, never fails to depict the angelic champion as a beautiful young man with a severe countenance, winged, and clad in armour or in white, bearing lance and shield with which he combats the dragon. St. John the Divine describes the Archangel Michael (Rev. xii. 7) fighting at the head of his heavenly warriors against the dragon and his host. St. Jude describes him as contending personally with the Devil about the body of Moses, as if the very ashes of God's servants received the protection of high heaven. Not unfrequently St. Michael is represented with scales wherewith to weigh the souls of the risen dead for the meting out of eternal justice. After the dispersion of the Apostles to preach the Gospel of Christ to the heathen, St. Philip went to Phrygia,, where he found, in the city of Hieropolis, the people worshipping a huge dragon which was the chief god of the Phrygians. Taking pity on their degradation, the apostle exorcised the dragon in the name of the holy cross which he held in his hand. The vile beast immediately glided from beneath the altar, but ere it was vanquished it breathed forth a stench so poisonous that the people around fell dead, among them the king's son, who fell lifeless into the arms of an attendant. The Apostle immediately restored the prince to life, which so incensed the priests of the false god that they seized upon him and hurried him away to death. He was crucified, and stoned as he hung upon the cross - a worthy martyrdom for a disciple of the crucified Christ. St. Margaret, who has been taken as the type of female innocence, was a beautiful maiden wooed by the Governor of Antioch, and for refusing to wed him was cast into a loathsome dungeon. Here she was visited by the Devil in the shape of a hideous dragon, who, failing to influence her in favour of her pagan suitor, is said to have swallowed her whole, but was forced to disgorge her from his wicked maw when she made the patron saint of Lyme Regis, and on the dragon and wounding it with a cross. Perhaps the most widely known of legends of this class is that of Tarasque, the dragon of the Rhone, destroyed by St. Martha. This fabulous beast gave its name to Tarascon, a quaint old city of Languedoc, towards the mouth of the river, and which has been immortalised by the illustrious French writer Alphonse Daudet. His work is an extravagant satire on the Provenšal character, and pretends to relate the Adventures of Tartarin of Tarascon, who is represented as a sort of minor Don Quixote. The fearful Tarasque is described "with eyes aglint and claws like the horns of a bull, coming in a thunderstorm across the bridge of Beaucaire, all scaled in crimson and gold, a monster four times as tall as the highest man, and more than twice that in length ; galloping fiercely and all the way belching forth great flames of fire and sulphurous smoke." This was the formidable beast which ancient legend asserts that St. Martha tamed with her own hand, and led gently away attached to her girdle - an allegory which doubtless symbolises a ravening paganism, which she dispelled by the sweetness of her eloquence and the self-sacrificing piety of her evangelising mission. The city of Tarascon is said to be built on the site of the dragon's den ; and in a cave beneath the spot where the altar of the church is now fixed the bones of St. Martha were discovered in the eleventh century. The effigy of the terrific Tarasque is still borne in the procession through the streets of the town on certain days of high festival. At Aix is shown the fossilised head of some extinct Saurian, unblushingly presented as the veritable head of the dragon slain by the piously fearless St. Martha. The story of St. Romain, or Romanus, is of the seventh century, and runs in this wise. To rid Rouen of the dragon Gargouille, which long had troubled it, Romanus on Ascension Day took out of prison a condemned criminal, and ordered him to go and fetch the dragon. The criminal obeyed, and the dragon, following him into the city, walked into a blazing fire that had been previously prepared, and was burnt to death. King Dogobert, to commemorate the event, gave the clergy of Rouen the privilege of pardoning a condemned criminal on Ascension Day - a right which was exercised for centuries afterwards, and so served to keep the legend green. It is significant that the name of this destroyer is given as Gargouille, which means a "waterspout," because there is a tradition that St. Romanus was a benefactor who built an embankment along the Seine which had the desired effect of protecting the surrounding country from the periodical floods that had formerly been the constant dread of the inhabitants. At Ploermel in Brittany an ancient stained-glass window of the church tells the story of St. Armel, a British saint born at Glamorgan, who flourished there in the reign of the Frankish king Childebert, at the same time as St. Samson. The story is pictured in eight compartments, in the fourth of which Childebert is seen at the door of his palace dismissing Armel, who has undertaken to deliver the land from a dragon ; in the next panel the saint is shown fearlessly meeting the dragon and putting his stole about him : and in the next we see the monster being led to the river and precipitated into the waters of the Seiche. The whole composition is supposed to represent a fragment of sixth-century history, and the dragon probably symbolises a tyrant named Conmore who usurped the throne of Brittany. St.Samson , Archbishop of Dol, was also famed as a dragon slayer. The most curious story of a dragon occurs in the legend of St. Simeon. The saint was famous for the holy life he led as a hermit, for his severe fasting, and the many strange ways in which he sought to subdue and mortify his poor body.

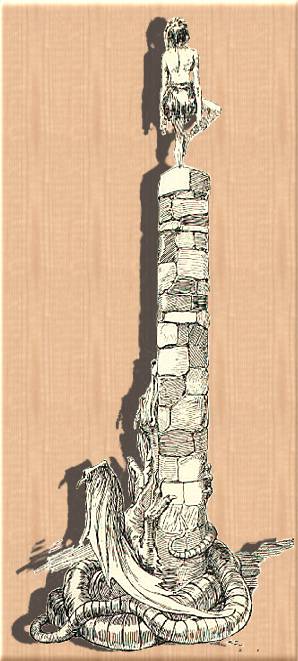

loins, and drawing up with a rope the little food he required, he was looked upon as a very holy man, by whose piety many miracles were worked. According to The Golden Legend, a book containing the lives of saints, written seven hundred years ago, a dragon had its dwelling near St. Simeon's pillar in the desert, and was of so venomous a nature that nothing grew for miles around its cave. The dragon met with an accident ; he got a stake through his eye. So coming all blind to the saint's pillar, he placed his wounded eye upon it for three days without doing harm to anyone. St. Simeon ordered earth and water to be placed on the wound, which being done, out came the stake, a cubit in length ; and when the people saw the miracle they glorified God, and ran away for fear of the dragon, who arose and adored for two hours, and then returned to his cave. The lives of the saints are full of wonders like this ; but the strangest part of the story is that a saint of antiquity should have shown a kindness to a dragon, usually the embodiment of Evil Unpardonable. For when these old tales were invented, the forgiveness of offenders against divine law was not always popular. But the humility of St. Simeon Stylites was exceedingly wonderful. Tennyson, among his English Idylls, has a poem on his great penitent, and makes him exclaim in self-deprecation : "I,

Simeon, whose brain the sunshine bakes ; St. Hilda, Abbess of Whitby, has sometimes been numbered among the dragon slayers, though more fitly she should have been classed with St. Patrick as a snake ridder. St. Patrick, we learn from grave and reverend chroniclers, betook himself to the summit of a commanding mountain in the west of Ireland - afterwards called Croagh Patrick - and from that height addressed all the snakes and toads of the Green Isle, decreeing their immediate and permanent banishment from the shores of that favoured land. The good St. Patrick at least spared the lives of the objectionable reptiles, whereas St. Hilda, the Yorkshire saint, had neither mercy nor toleration for them. Being grievously tormented by a great plague of snakes in the vicinity of her cloisters, she prayed so earnestly to heaven that the existence of these dangerous creeping things might be ended, that the offending snakes were forthwith turned into stone. For the corroboration of the legend, stone (fossil) snakes are sometimes turned up at Whitby, but not one of the poor petrified creatures can boast a head among them ! Of all the saintly legends in this category none is more beautiful or richer in poetic fancy that that of St. Leonard. In the far-distant days when Sussex was a vast forest, a hermit took up his abode there. He was called Leonard, and he had been a courtier to Clovis, the Frankish king, and afterwards a disciple of St. Regimus. At first nothing disturbed the serenity of the hermit's solitude ; but when a multitude of nightingales began to haunt the vicinity of his cell, the pious hermit found their singing a distraction to his meditations and an interference with the performance of his sacred offices. So he bade them depart. The nightingales obeyed his behest, and have never returned to that spot ; so that, year by year, while every other copse and thicket in the country has resounded with the songs of nightingales, St. Leonard's Forest has remained silent. But the saint soon found that the forest contained another denizen, a dragon of immense strength and great malignity, the dread of all the villages for miles around. Many and fierce were the encounters between the saint and the monster, and although the former was often sorely wounded, he drove his antagonist father and farther into the recesses of the forest, till at last the creature disappeared in the underwood and was thought to be slain. The scenes of these successive combats are revealed afresh every year, when beds of fragrant lilies spring up wherever the earth was sprinkled by the blood of the warrior saint. But the marvels of mediaeval mysticism in this case are not stranger than the sequel to the legend - a circumstantially reported reappearance of the dragon in Puritan times, centuries afterwards. A work published in 1614 gravely reported that at Faygate, near Horsham, had appeared that year a terrible and noisome serpent, nine feet in length, "with a quantity of thickness about the middest," and having on each side two great bunches as big as a large football, which it is thought would grow into wings." So rare a monster was best destroyed without delay, so it was at once hunted with the aid of two powerful mastiffs, both of which it speedily killed and devoured. And though we are informed in veracious print of the "many slaughters, both of men and cattell, by the strong and violent poyson of this creature lurking in St.Leonard's Forrest, only thirty miles from London, in this present month of August 1614," the final disposition of the monster is left unrevealed. Which is a not unfitting ending to a tale very engaging, and one which offers so wide a field for speculation. Notwithstanding the prevailing idea that for a successful encounter with a dragon it requires some saintliness of character on the part of the challenger, there is a Herefordshire legend of a dragon, which once infested Mordiford on the Lugg, being slain after a furious combat by a condemned malefactor. It must not be overlooked that dragon-lore in its religious associations carries us back beyond the Christian dispensation, as the title and subject of one of the apocryphal books remind us. The Book of Bel and the Dragon is really an addition to the Book of Daniel. The dragon has been associated with the history of many saints, but with the story of only one prophet. Briefly the story is this : The image of Bel was one of the objects of worship set up in Babylon, and the royal edict ordering the people to bow down to it was disobeyed by the prophet Daniel. The king expostulated with the man of God, pointing out in proof of the deific nature of the idol the amount of food it consumed. Daniel replied by asking permission to arrange a test. The food was prepared for the idol and the doors of its temple were locked and sealed ; but Daniel, suspecting trickery on the part of the priests, had also secretly strewn the floor very lightly with fine ashes. Next morning the seals were found unbroken and the food gone. Examination, however, disclosed the marks of naked feet on the floor. So the priests were convicted and put to death. There was also in Babylon a great dragon which was universally worshipped and regarded as divine. To this Daniel not only refused to bow the knee, but offered to kill the beast. Upon obtaining the king's permission to make the attempt, the prophet prepared a concoction largely composed of pitch, and threw it to the dragon. As a result the dragon burst asunder. The infuriated people demanded that Daniel should be thrown to the lions ; but, as we read, under divine protection he remained in the den of the savage beasts quite unharmed. The story is full of palpable errors and extravagances, and has not been accepted as an inspired Scripture. It was probably written in the first century before Christ. Something very similar to the Bel and the Dragon story has been found in Arab legends with Alexander the Great for the hero.

|